TSD

ARTIST SERIES

JOEL BOLONICK

Neal und Mary

I was really motivated to intensively explore color photography after seeing a poster in a coffee shop by Joel Meyerowitz from his book Cape Light. Suddenly I had found someone who seemed as obsessed with color possibilities as I was and showed that contemporary film materials could be used to quite accurately depict the emotional content of color. It also led me to take up the view camera.

After I had studied photography at the San Francisco Art Institute with Henry Wessel, my work career has largely been in research related to biotechnology. Neal and Mary was taken with a 4X5 sheet film camera on a hot morning in Chicago. At the time of the photo, Mary was my girlfriend. She is now a lecturer in sociology at the University of California (Berkeley). Neal was a close friend of myself and Mary. Sadly, he died of AIDS several years after this photo was taken.

I had an odd realization about this photo today. Many elements of it remind me of aspects of 17th century Dutch interior paintings, such as those of Vermeer, which has long been one of my favorite art periods, only instead of depicting comfortable Dutch middle class life, something more ambiguous and possibly troubling appears.

THERESE DEBONO

Emma

This summer Emma was raped in her own home by a nurse whom she trusted. The abuser groomed her from her hospital stay and beyond and this led to the rape. Since then, she has been waiting for a court case to get some justice. However, nothing has been done yet. She has been told to stop talking about her abuse. She has been told to shut up. She has been told that she has taken this too far. She has been told that what happened was her fault. This nonchalance towards abuse must stop. Somehow, we do not take rape seriously. We just let it pass us by.

I told Emma not to shut up. I told her to keep fighting for herself and indirectly for us all females. I told Emma that those who tell her that she must shut up, are the ones who are also guilty of her abuse because they are enabling the bad behaviour when they tell her to shut up. Shutting up is not OK!

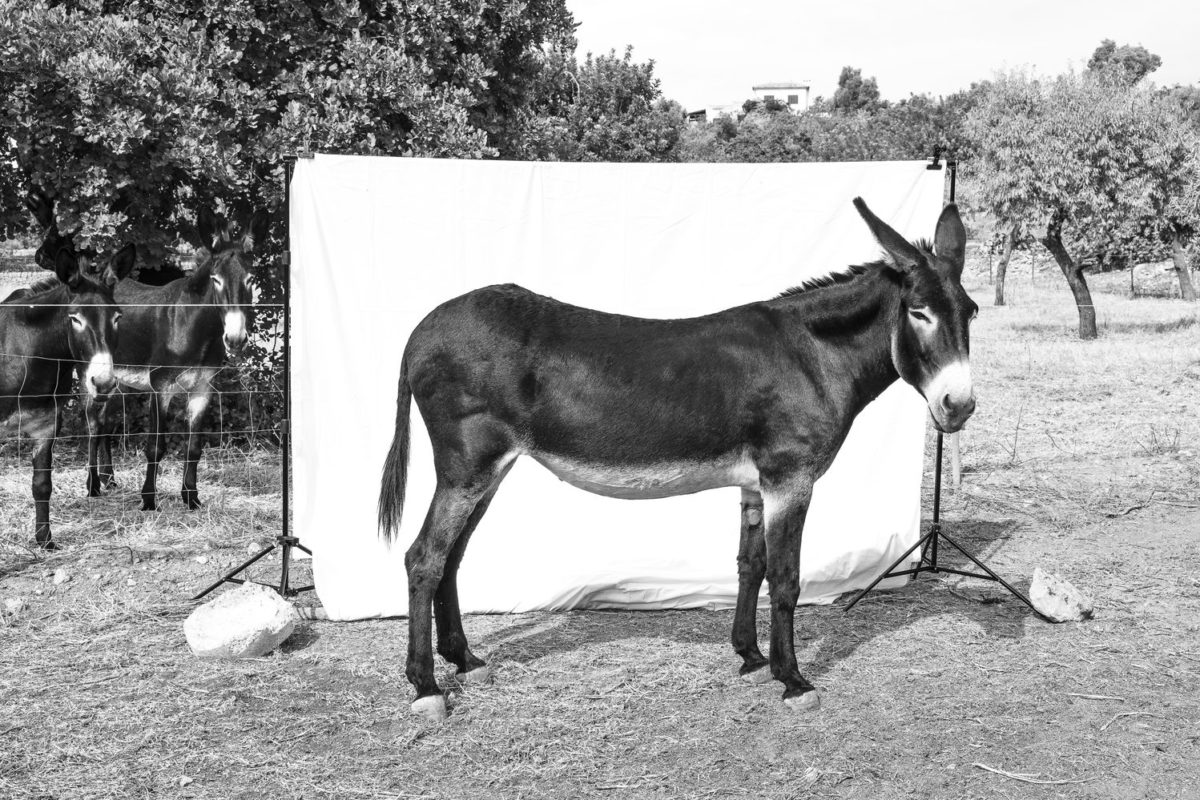

SIBYLLE FEUCHT

Donkey Business

Portrait of the female Ase Balear Pepa de Cas Retat, who is the leader of the herd.

The Ase Balear or Mallorquin Donkey is an own race that is close to extinction, as most of the donkey races world wide. This is due to the fact they lost their purpose — carrying heavy things or pulling carts.

AARON RICKETTS

RED

A Serious Case of Something That Should Probably Be Checked Out But In Reality You’ll Just Try To Sleep It Off (RED).

SITARA THALIA AMBROSIO

Fragile as Glass

Julian, 19, lives in Lviv and studies architecture. He is also a part time model. In his activism he works a lot on LGBTIQ* issues and together with some friends, recorded several podcasts on the topic in 2020.

“Sometimes I feel a little scared, considering that we have a war going on in our country right now. You can feel it in different ways. Every day it becomes more and more. You hear what your friends are saying, what your beloved partner is saying. For example, the day before yesterday, in the western part of Ukraine, where my partner lives right now, a rocket came down very close to him. I started to panic and I didn‘t know what to do while he was probably in danger.”

HERMANN BREDEHORST

Surface – Spree

It is the time of the Corona stop. Sitting in a house near the river, the days go by with the handbrake on. But the river keeps flowing, to Berlin and some molecules maybe even to New York.

So the Spree, who actually lives there, what does it look like?

The theme of the river thus suddenly becomes a narrative space for a photographic journey that consists of different episodes, in which each story brings forth different stories and the lives of the protagonists seem to intertwine, probably without ever meeting each other. It is the course of the Spree River that connects these stories on their winding trail.

ANNETTE LEMAY BURKE

Memory Building

Chuck’s Corvette

My parents died within a few months of each other. They lived in the same house for 60 years, from the day they were married until their deaths. Once they were gone, I was left with my grief, memories of our lives together, and all their possessions, including a welloganized archive of family photos.

In my series, Memory Building, I projected those vernacular photographs onto the surfaces of my childhood home in the same locations that they were originally made and rephotographed the scene. By fusing photos from the past onto the presentday walls, I unearthed six decades of engrained memories and captured my family’s vanishing presence that once permeated our midcentury suburban home — the container for so much of my personal history.

Constructing the projected tableaus made the memories more substantive for me, provided solace for my grieving and created a new family pictorial legacy for future generations. With so many formative experiences rooted and intertwined within this building, saying goodbye to it was also saying goodbye to my parents. Even as the rooms were literally whitewashed in preparation for new owners, my memories continued to resonate within the walls.

KASPAR CHRISTIANSEN

In a time

Spaceshop

In a time, is a project that explores human expression. By portraying and documenting moods and experi ences that are created in time and space around us. The moments arise by observing the familiar and by trans forming them into new unknown impressions, with an aura of mystery. They become stories, which are often little overlooked actions, between actions. Actions of our complex processor and dynamics we as humans step in and without knowing it, our emotions become visible in the works.

The works are based on my own life and experiences and have roots in both the spiritual and our society. Working in the vein of phenomenology, I examine the small pockets of information about how we experience and recognize the world through consciousness, bodily and sensory.

By creating a common starting point, in the form of the familiar, a space is created around the works that in vites the viewer in, based on the same premise.

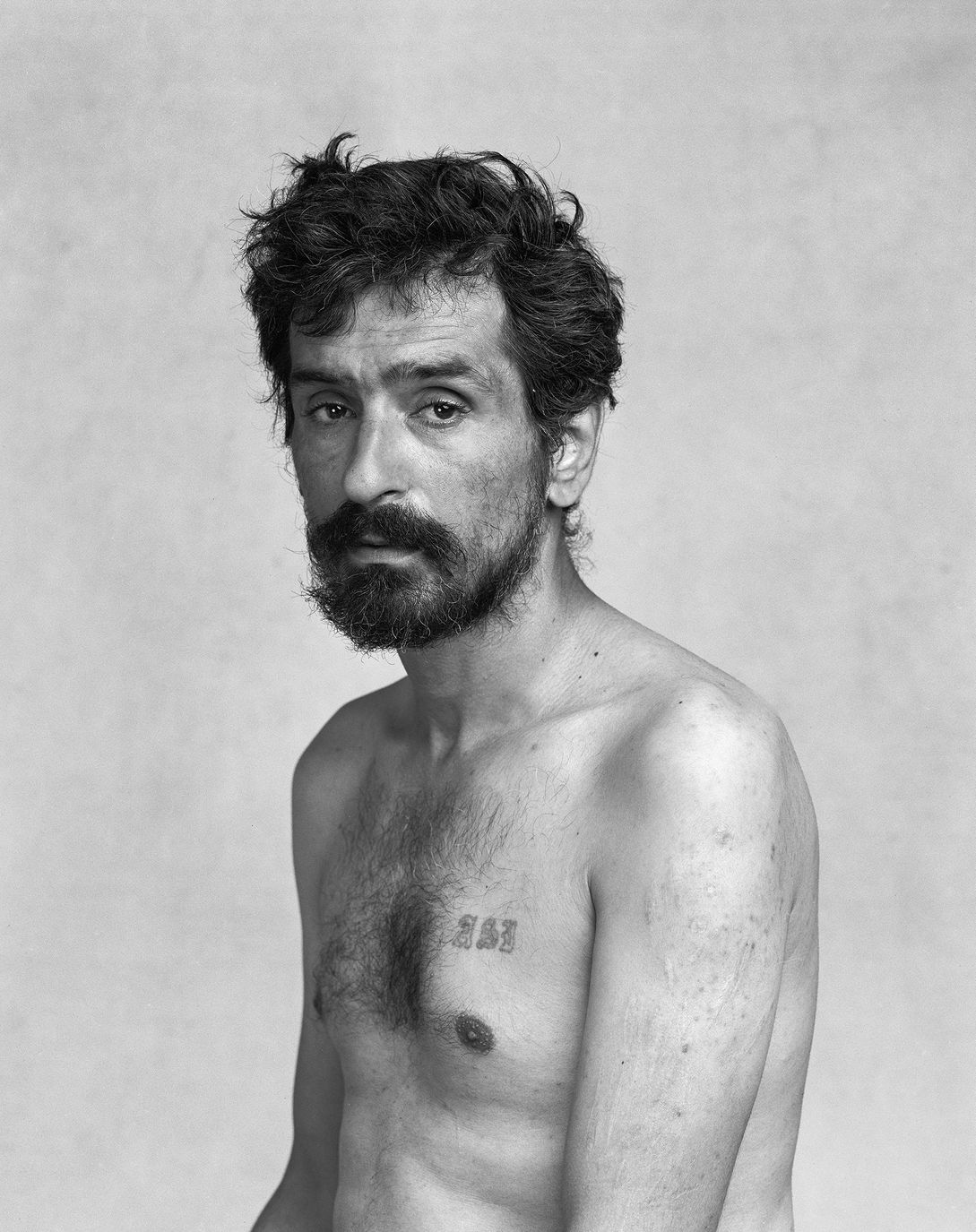

MASSIMILIANO CORTESELLI

Contrapasso

In the »Inferno« of the Divine Comedy, Dante sets out on a journey through hell with the ancient Roman poet Virgil, meeting deceased people he knows personally or from history books. These suffer punishments that are similar to the sins they committed or the exact oppo site. That punishment he calls: contrapasso.

Now mankind is experiencing its own form of contrapasso. Wildfires redraw every year the landscape of the mediterranean region. A region that stood for fertile soil and mild climate is now threatened by desertification and droughts, which mainly affect lower income areas and the economically disadvantaged rural population.

The photographed protagonists and their stories are depicted as archetypes — like those in Dante’s Inferno. Their contrapasso could become ours.

AMILTON NEVES CUNA

Madrinhas de Guerra

Amelia

Madrinhas de Guerra or Godmothers of War is a project telling the story of the Mozambican women who took part in the National Women’s Movement from 1961–1974. These women were sponsored by the Portuguese government to provide moral support to the soldiers fighting on the frontlines of during the Mozambican War of Independence. Through letter writing campaigns to soldiers — many of whom they never actually met — the Madrinhas de Guerra played a critical role in the psychological support to the colonial armed forces.

Some Madrinhas went so far as to meet and regularly visit the soldiers to whom they wrote letters, developing deep relationships sometimes leading to promises of marriage when the young men returned at the end of the war. In exchange for their support during the war, many of these women were rewarded with influential positions in society and the upper classes and some were even given houses by the Portuguese government.

In 1974, when the war of independence ended with a ceasefire agreement between the Mozambican FRELIMO forces and the Portuguese government, the National Women’s Movement officially ended. However, the Madrinhas de Guerra were ostracized within Mozambican society for their role in supporting the colonial forces. The Madrinhas de Guerra project reflects on this very important — but often forgotten — piece of history in Mozambique by visiting the homes of the Madrinhas de Guerra who still live in Maputo today and embody the past of the opulence experienced during the support of the Portuguese government and the subsequent marginalization felt after independence.

CORINA GERTZ

The Averted Portrait

Corina Gertz photographs women in traditional dress from all over the world. She is preoccupied with the threat to cultural heritage posed by globalisation. Her focus is on the seemingly quieter side of the portrait, the back views.

Fascinated by both Dutch portrait and still life paintings of the 17 th century — with its detailed, haptically tangible compositions against an unfathomable warm darkness — influenced her compositions.

But her subjects remain hidden; the clothing alone communicates. Many of the images are composed of inherited pieces, which hold history and tradition. They are manifestations of the preservation of traditional knowledge, conventions, customs and practices.

Corina works hard to represent this cultural heritage with respect to craftsmanship, origin, family and social status, and thus reveal something about the identity of the wearer, without revealing their individuality. On the one hand, they are community portraits. On the other hand, through the detailed presentation of the clothing, there is an intimacy with an individual, their aesthetic, political, social and cultural contexts.

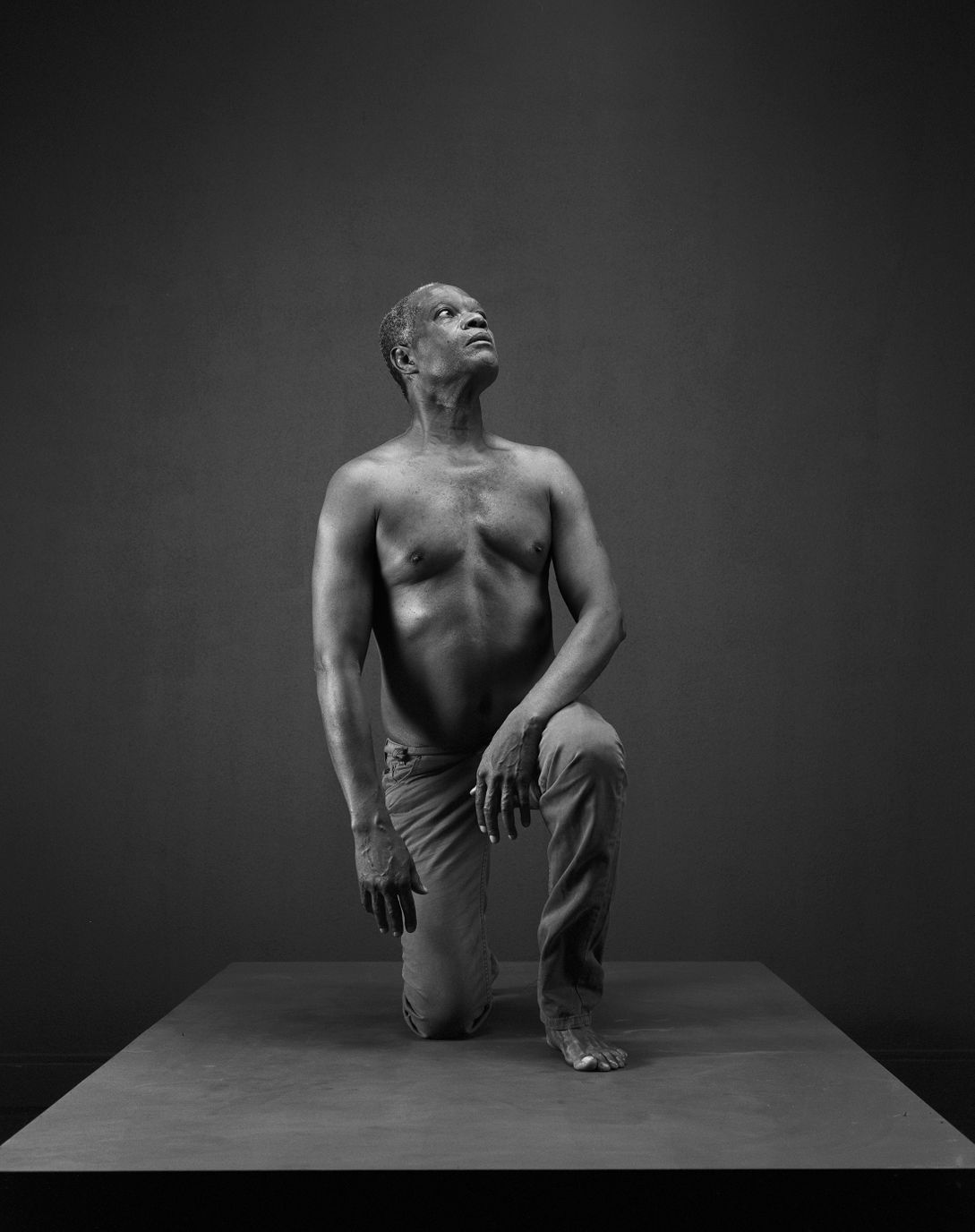

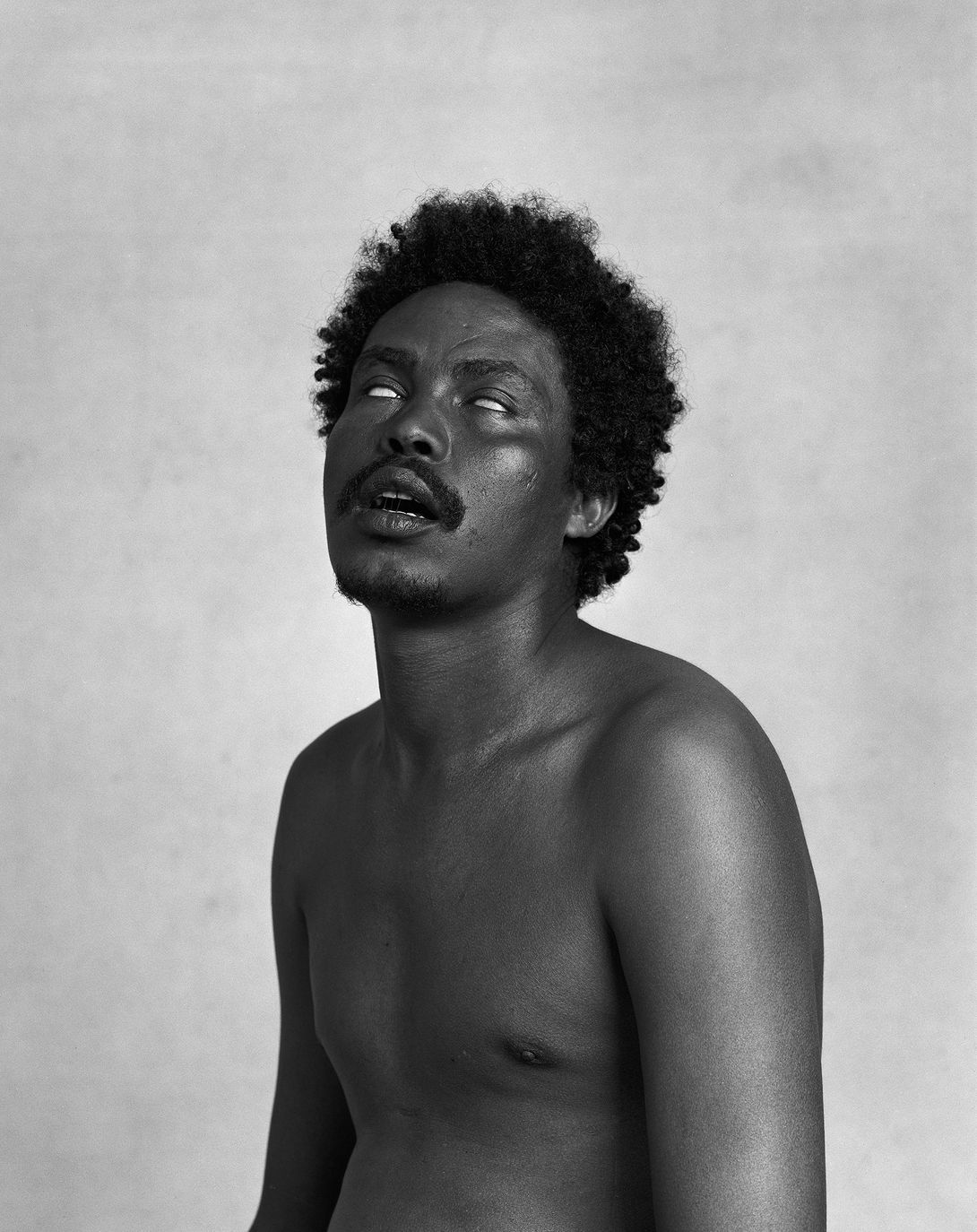

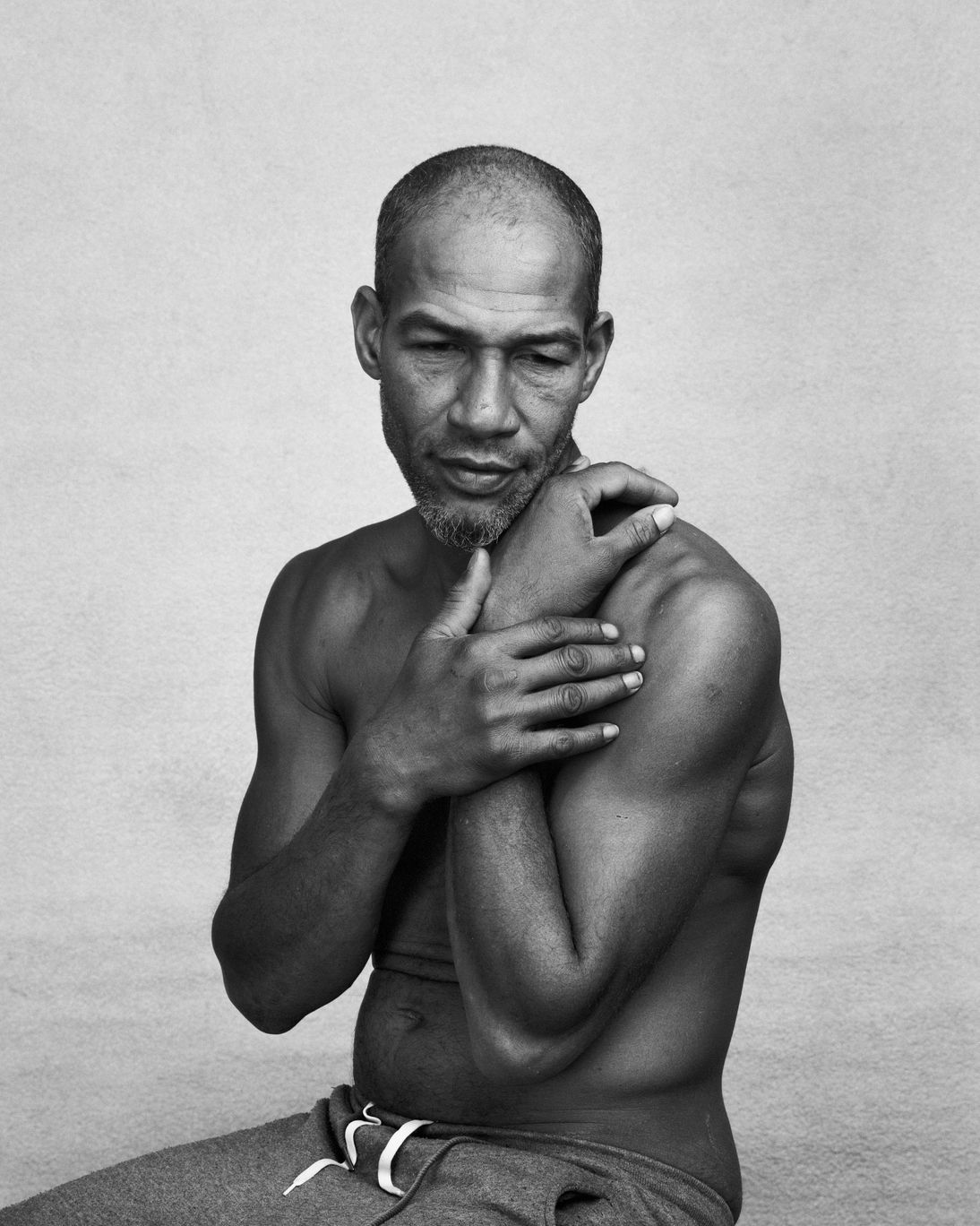

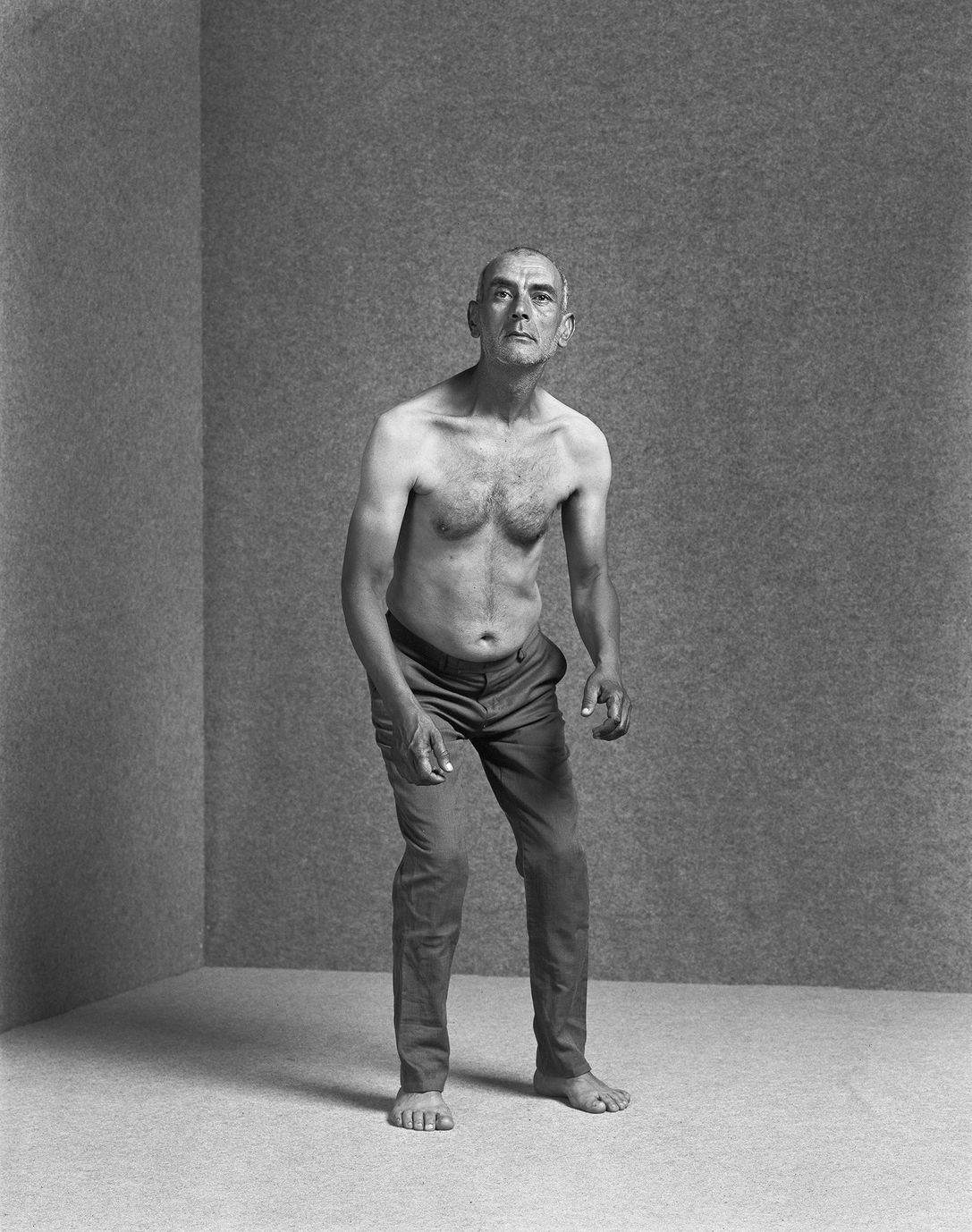

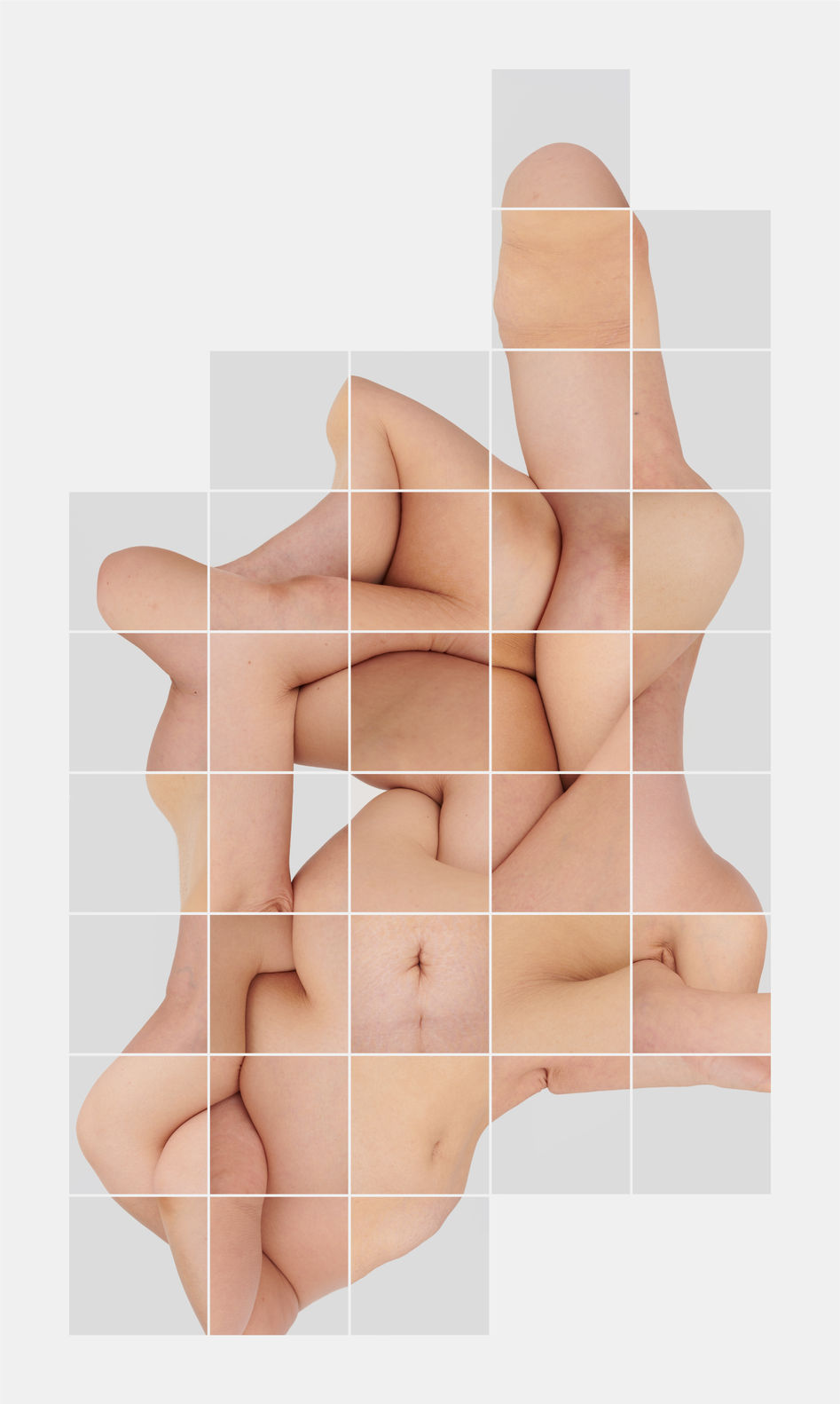

MILAN GIES

Composition

“Milan Gies was one of the participating artists in the exhibition RAUW, which was on display from January 22 th to May 22 th 2022 in the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam. His series Com position (2022) was an indispensable addition to the theme of our exhibition; a realistic view of the human body. In his approach to the human body, Milan focuses on the physical and mental traces that life leaves behind. The central question is: to what extent can you see traumatic experiences reflected in the way someone looks or moves. For his photo series, he has built up a longterm relationship with homeless men in and around Amsterdam, whom he photographed in his studio. The work shows Milan’s artistic qualities and his respectful and deeply human view of those who dwell in the margins of our society.

Milan’s photographs show painful human experiences without sensationalizing them; it is this understated and personcentered approach that gives Composition such a great expressiveness.

The more than 50,000 visitors to the exhibition spent a long time reflecting on the photo series and have repeatedly expressed their emotional experience when seeing the photos. This testifies not only to the quality of his photographic work, but also to Milan’s

ability to make people look at our society and our fellow humans in a different way. At a time when ‘success’ and productivity seem to be the highest achievable goals, people who don’t live up to this ideal are often ignored or disapproved of. Milan moves against the current by seeing and acknowledging especially these people in all their humanity. Thanks to Milan, they are not erased from history.”

Nathalie Maciesza

Curator contemporary art

Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam

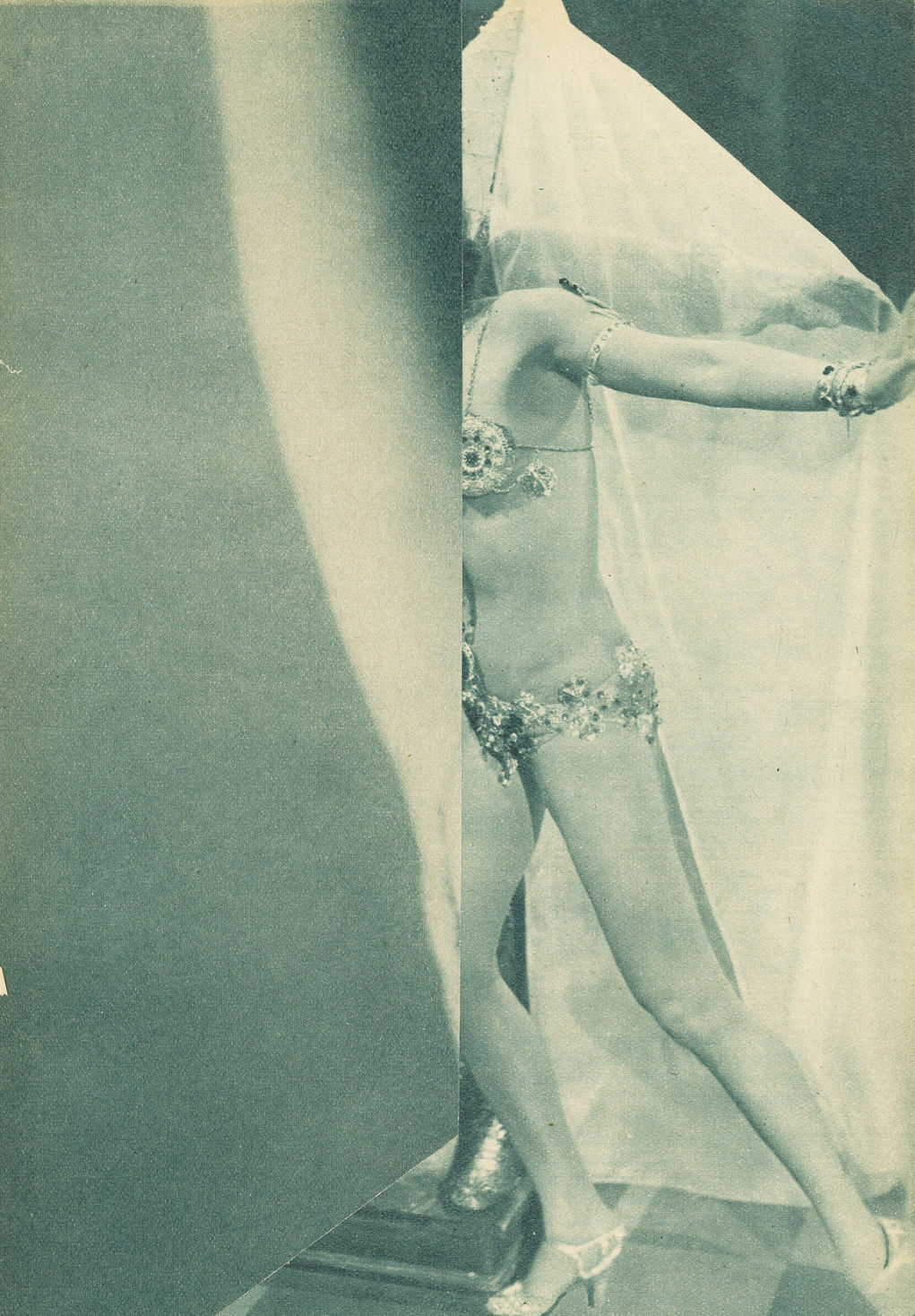

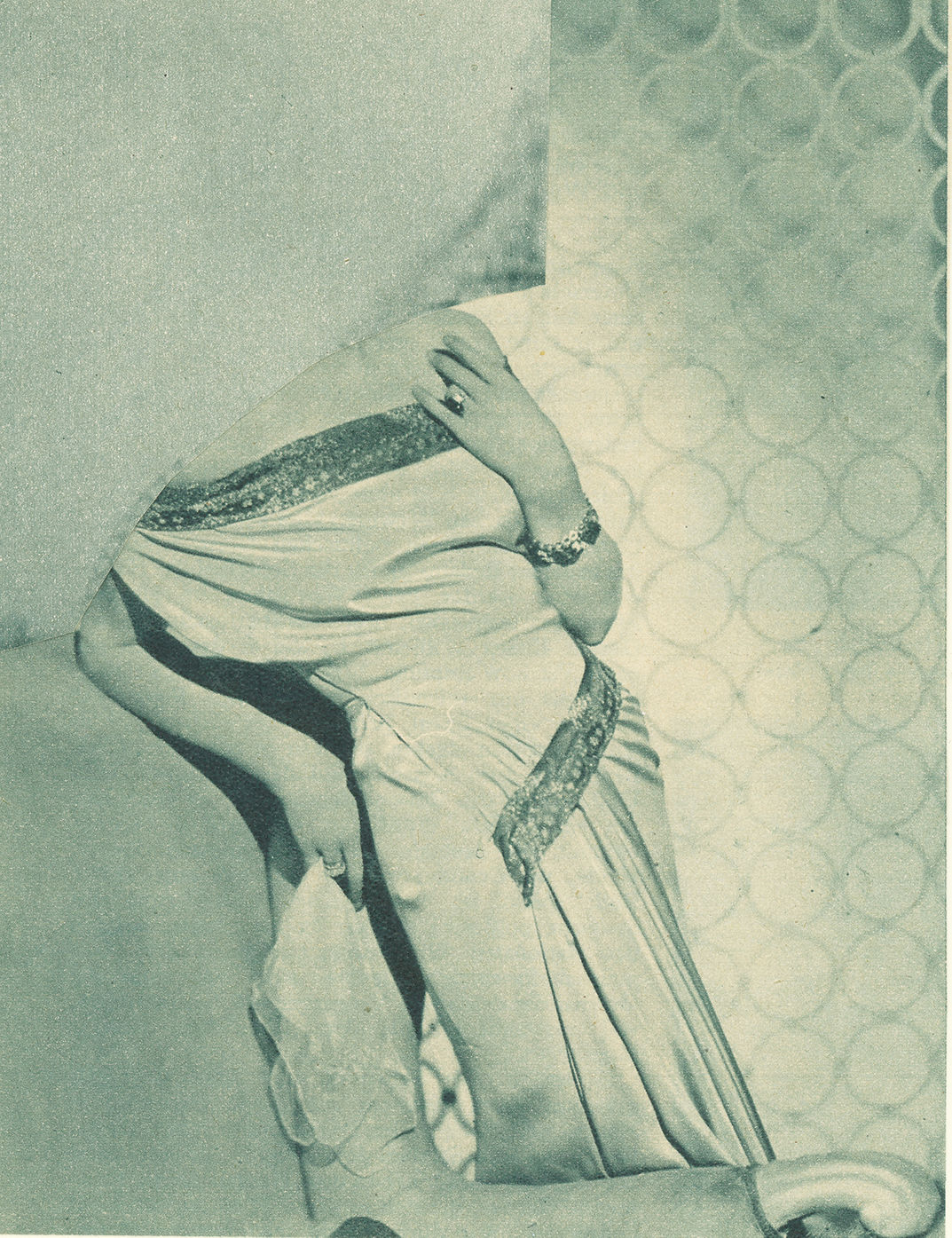

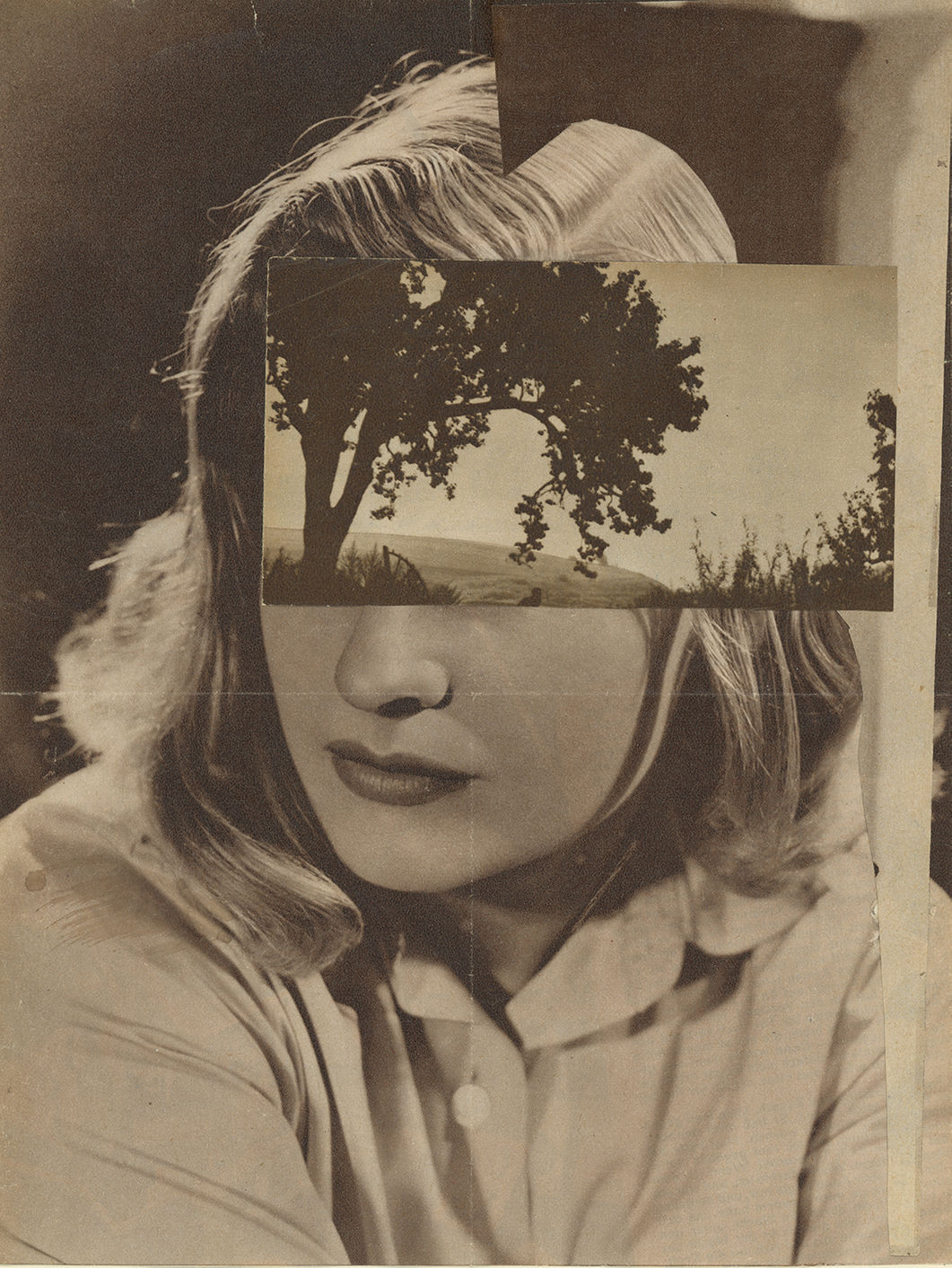

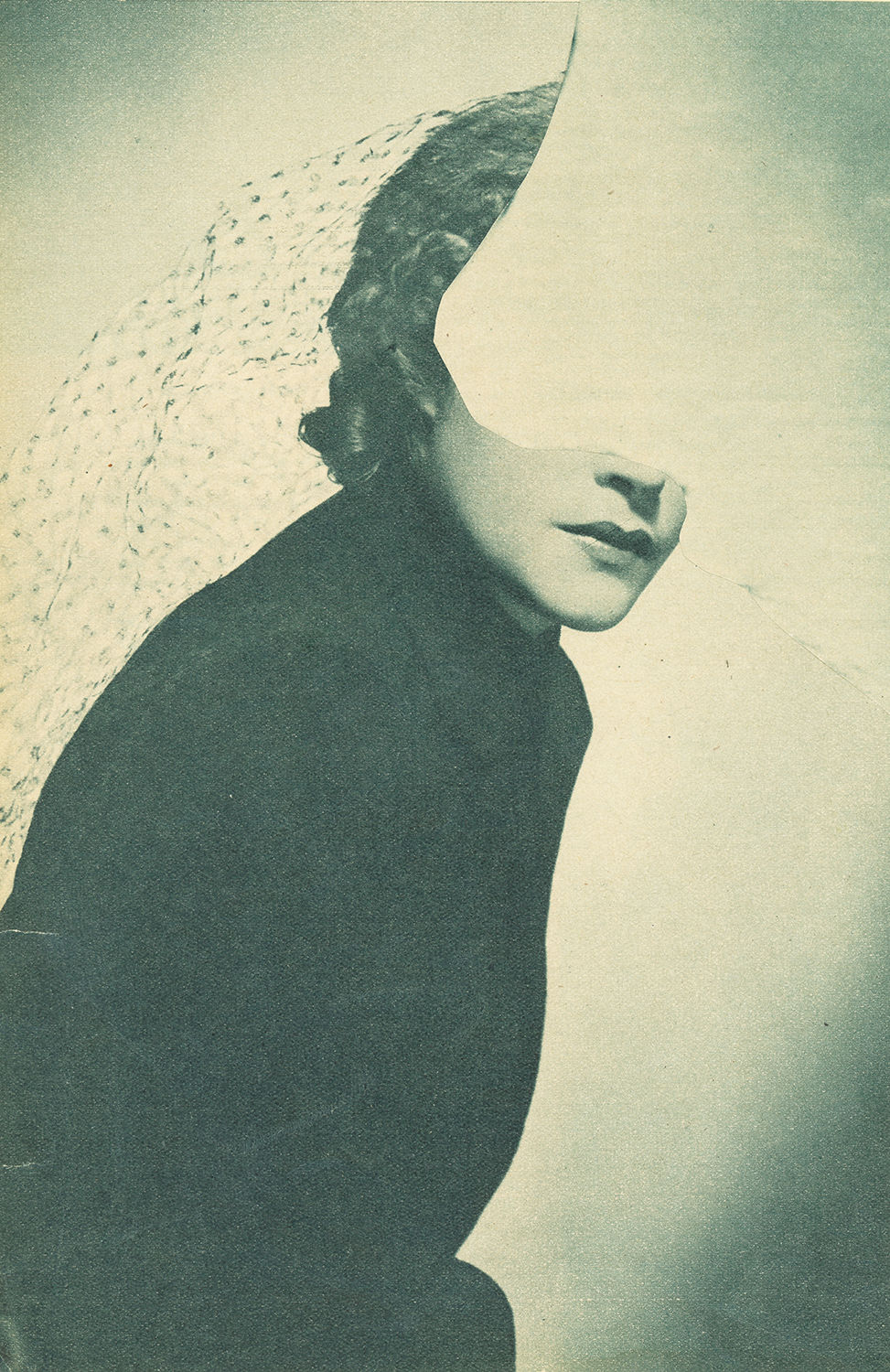

EVA GJALTEMA

Hiding/Hidden

The photo collage series Hiding/Hidden is about women who feel like they should be hiding and protecting themselves against an external force or are being hidden by an overruling force. Many women have to fight against this power play on a daily basis. A contemporary and historical issue that I made visual with cutouts from 80 year old German Cinema magazines.

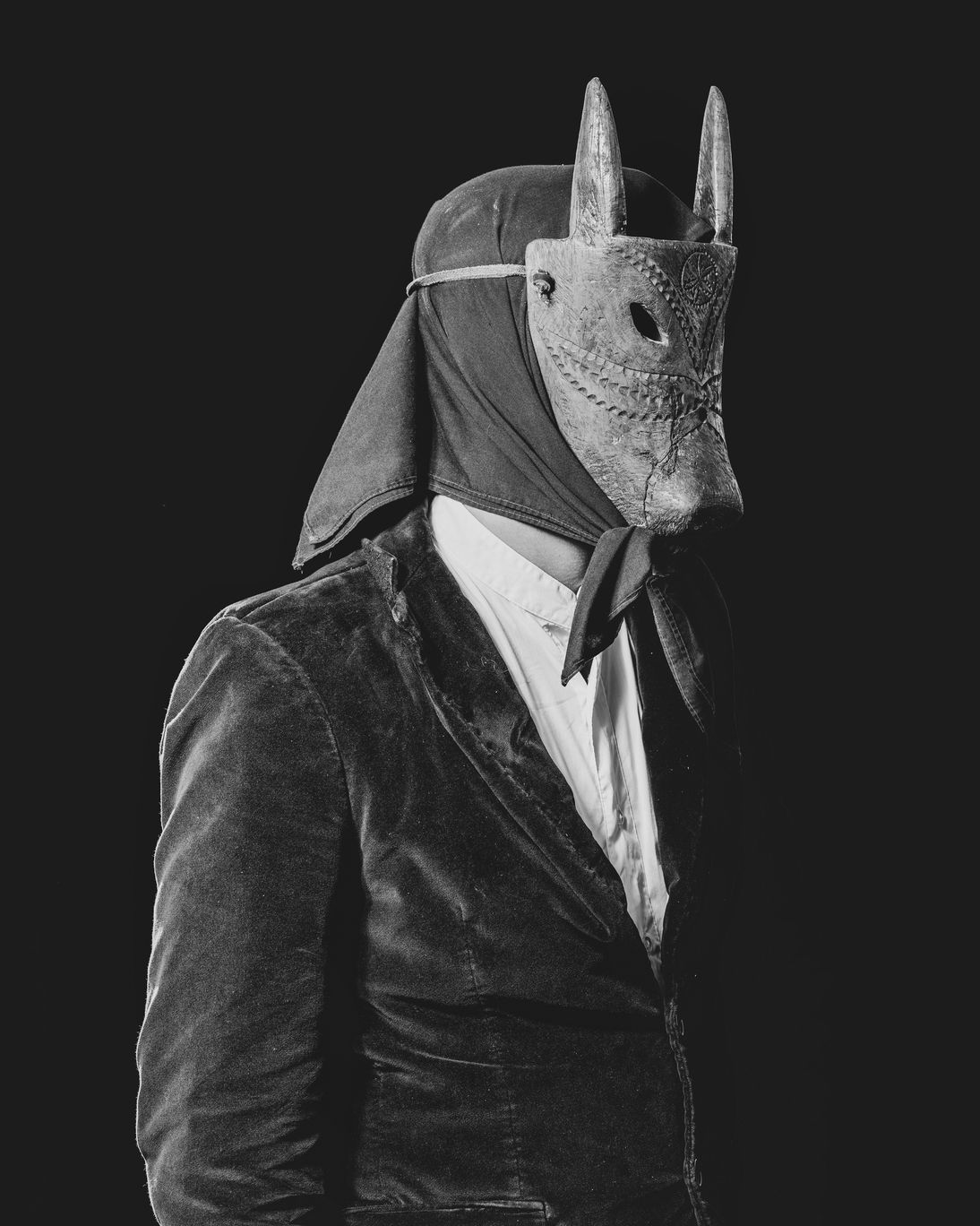

ANDREA GRAZIOSI

Animas

In the center of Sardinia, in different villages of the territory of Barbagia, strange and archaic traditions live well anchored.

Practiced by the inhabitants, ancient cults represent an intense and brutal relationship that man maintains with the wild and carry a mystical, spiritual and sacred value, with a cathartic and liberating goal.

These costumes belong to a time that does not belong to us, to hide is a destiny, the hyphen of a disturbing relationship between the beinganimal and the divinity; to wear a mask means to metamorphose into the form of another entity.

The threatening and disturbing that these masks produce does not have the function of frightening the other, but it is to provoke a relationship with the other.

The inhabitants of this region use the expression Animas to define something that has neither time nor body, once disturbing, wild, is what is specifically nonhuman and serves to live an experience.

GERALDINE HAAS

The Bold and the Beautiful

Portrait of me and my mother

The title The Bold and The Beautiful, borrowed from an American soap opera, deals with the lifestyle of the rich and beautiful. I myself grew up in Zollikon on the socalled Gold Coast of Zurich. With a mixture of documentary and staged photography, I approach the moments that show alienation and familiarity at the same time, and in which we rediscover our society’s longing for flawless beauty and eternal youth. It is the ambivalence that serves me when the stereotypes in which we pose break open and the view of the abys ses associated with the exaggeration is revealed.

I am part of the pictures as I live among the rich and beautiful, but these are not selfportraits. My gaze reflects society’s desire for pictorial selfportrayal, which is intended to counteract transience. In this sense, the embellished aesthetics of my photography and the choice of motifs based on the classic genre of painting are a means of expressing my own ambivalence between selfimage and selfdiscovery.

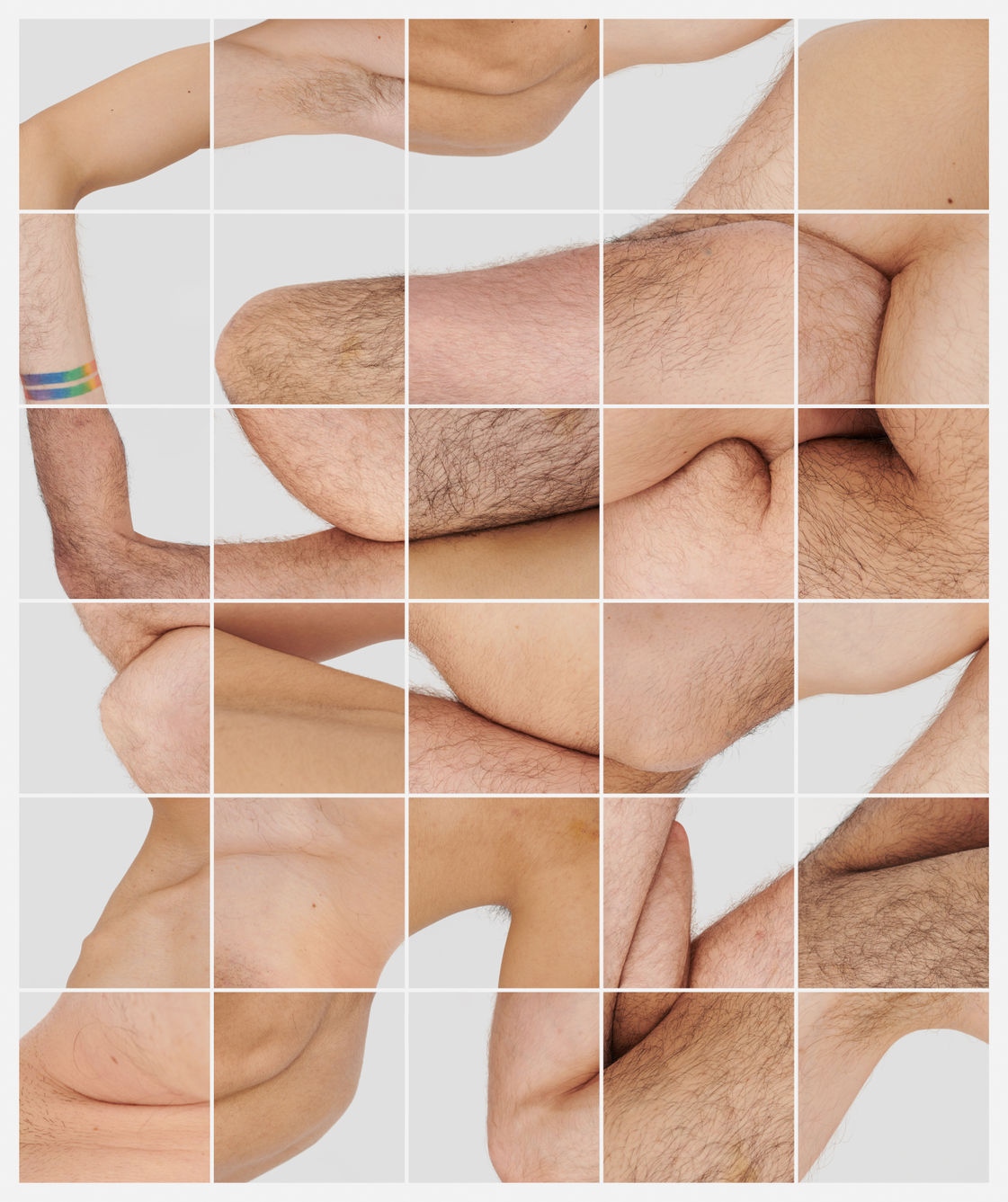

SHINICHI ICHIKAWA

Mistakes connections

Mother ans Child

The starting point of this project is to equally consider diverse bodies. I took photos of people of any age, sex, body shape and race and they are juxtaposed and reconnected. The body of one person falls apart and is connected with another.

While one person is muscly, Another is amplefigured.

One person is born without the left arm, Another has large surgical scars.

One pregnant woman is three days before childbirth, Another has been diagnosed with an incurable disease.

One family is descendants of immigrants, Another couple identify as LGBTQ.

The bodies tell a variety of themes.

As they mix together, Many I are crumbled and develop relation ships with one another.

An unexpected problem that a person next to you have might be connected to your body.

It’s not always comfortable, but as long as we live in this world, we need to continue to engage with others, without viewing them as a single homogeneous monolith.

NANCY LUDWIG

In den Augen. Alle Zeit.

Rita Seredßus

The series In the eyes. All the time. (dt. In den Augen. Alle Zeit.) portrays the artists of the RambaZamba Theater. Founded in 1990, the private theater is based at the Kulturbrauerei in Berlin Prenzlauer Berg. Comprising twentynine artists with disabilities the ensemble forms the framework for a photographic examination of normality.

Real human situations cannot be divided into pairs of opposites. Healthy bodies — sick bodies, disabled — not disabled, normal — different. Differences and deficits are elements of human diversity, they fluctuate and are subjected to change; the majority of dis abilities are acquired.

The portraits raise fundamental questions about existence itself; they have a mirroring function. The connecting factor in human relationships and being human is negotiated with the help of debating feelings that we share and carry together. The uniting factor is the vulnerability that determines our core existence.

After Kant it is said that being human has value in itself, according to which it may not be subjected under foreign purpose. Based on this assumption, every human being within society is of equal worth. This worth should not be based on individual usability and function, but on unconditional human dignity and belonging. Accordingly, the demand for inclusion entails a comprehensive participation in social life and the overcoming of structurally exclusive conditions.

The portraits are reminiscent of Renaissance paintings in terms of form and content. Back then the human being was represented — for the first time — at the center of their own life. The neutral display and black background reinforce this effect, along with the universality humanness, selfdetermination and participation.

Due to their formal intimacy, the pictures tell something beyond the surface and allow a very dense, emotional approach on equal terms. The result is an exchange that refracts back onto the viewer’s own existence.

SUSANNE MIDDELBERG

Daylight

Magne van den Berg

In my portraits I am looking for honesty and vulnerability. I believe that vulnerability makes us nicer human beings and that this makes the world a little more friendly and more understanding. People who show themselves vulnerable give the other the confidence that they themselves may be who they are.

I am most fascinated when I can see opposite qualities of a person at the same moment.

I find this exciting because people are complex. I hope that the portrait touches something of the viewer himself.

In this series, I chose to use only daylight to make the image as natural as possible.

EKATERINA MUKHORTOVA

Lifeless

Face recognition and authentication systems are spreading widely and have already taken place in our mobile devices and on the streets of the cities. These systems now face different kinds of challenges from ones with ethics and control to another with security.

I have been shooting this project while taking part in collecting Face antispoofing algorithm data. The task of this technology is preventing false face verification by using a photo, video, mask or a different substitute for a face. Face anti-spoofing algorithm is based on neural networks so it needs huge datasets of different faces in masks and without them for best results. In this project I shot my self-portrait while taking an impression for silicone mask making, stages of mask making and my self–portraits in the mask. I also photographed printed photos of other people who took part in data collection prepared for maskmaking.

MICHAELA MAGYIDAIOVÁ

Transient Ties

Roadside shrine

One of the contemporary migration routes begins in Turkey, continues in Greece, and via Southeastern European countries towards Central Europe. Once, Greece was a starting point of a similar migration route, walked by Lena (in Slovak & Macedonian) or Eleni (in Greek), who was forced to escape her homeland. Lena’s up rootedness was a result of the Greek Civil War (1946–1949) fought between monarchists and communists, heavily supported by the UK and USA, as the West didn’t want Greece to be yet another country falling under communist regime spreading in Europe at the time. The communist side was receiving support from Yugosla via, Albania, and Bulgaria. Lena/Eleni was never repatriated to her native environment in northern Greece and reconnected with the Slav-Macedonian minority, into which she was born.

Transient Ties analyses the process of alienating oneself from one’s birthplace, whilst attempting to integrate within a new environment, which continues to occur to political refugees and migrants all over the world. Through this story, I collaborate with my grand mother Lena/Eleni, while exploring her identity, and the bonds between displacement & cultural heritage. The work contemplates what are the consequences of displacement, triggered by forced migration. The attachment to Lena’s roots vanished once adapting to a different culture, in former communist Czechoslovakia, where she lives until today (Slovakia).

Due to the Greek Civil War, thousands of children in Greece were sent to communist countries in Central & Eastern Europe to escape the war in their homeland. Intensely weakened by the Second World War, Czechoslovakia decided to accept up to 13.000 children coming from Greece, including Lena. Although the geopolitical and economic situation of both Czechia and Slovakia has significantly advanced since the late 1940s (the period of the Greek Civil War), political responses to contemporary migration, especially from out side of Europe, are mostly bitter.

ARSENIY NESKHODIMOV

Where are we going?

I started this project in 2022 in Istanbul, where Asia meets Europe. I took pictures mostly in Taksim Square, and within a few hours thousands of people from different parts of the world passed by me. This project lies at the junction of fashion photography and typo logy. There are already more than 200 backs in my collection, and the most beautiful thing about this story is that it can be continued indefinitely.

We often tend to make judgments about a person based only on his appearance, skin color or eye section, so I deliberately refused to use excessive visual information in this project.

I don’t know anything about my heroes, but, oddly enough, every back seems painfully familiar to me. Paradoxical as it may sound, but every nape has its own face.

I can’t say much about all these people, except that each of them is moving forward. In theory, this should fill me with some vague hope that we are all moving towards some goal, but at the same time, I have no idea where we are going and what for.

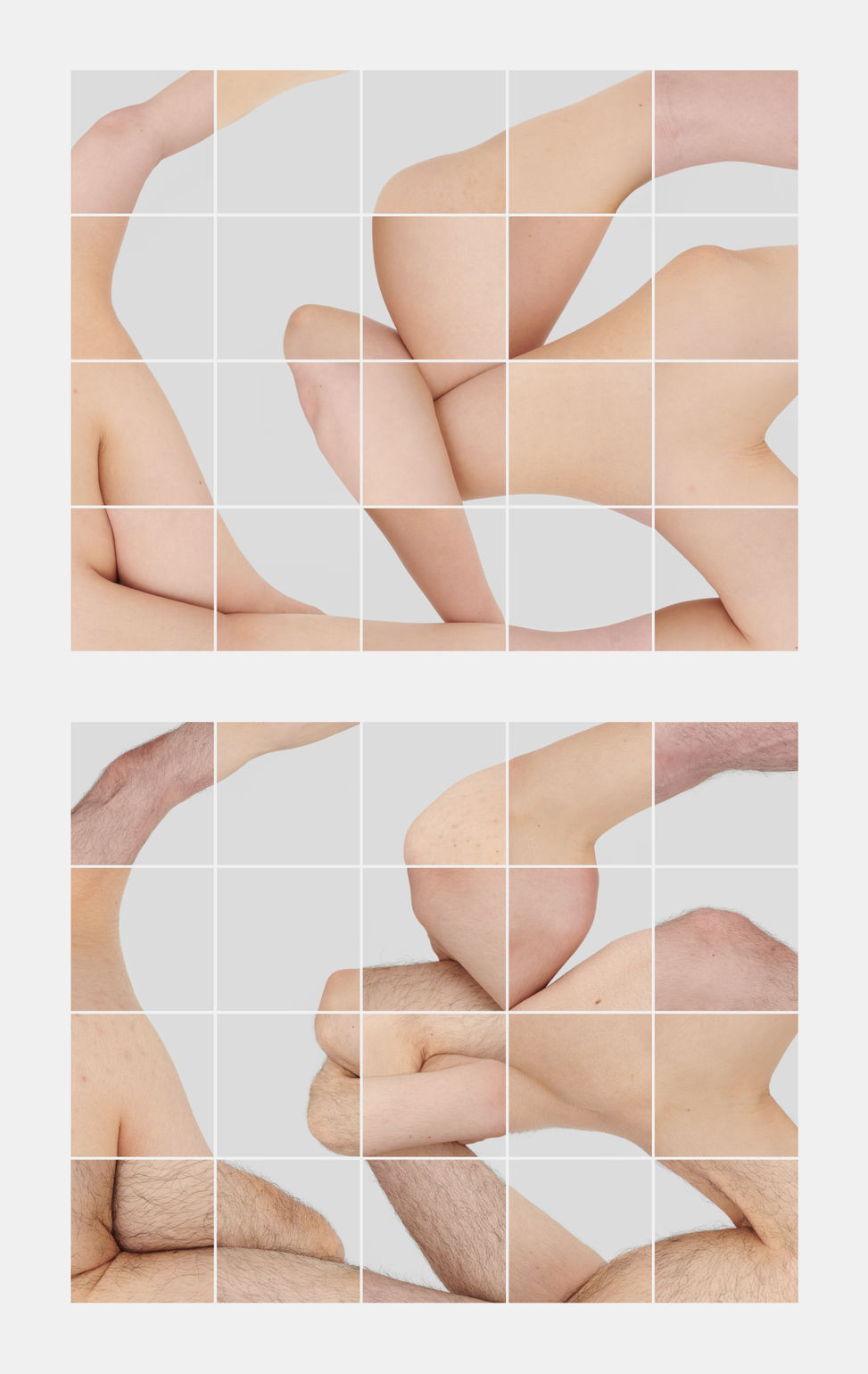

NICOLA PETRARA

Schiene

The back (schiene) is the part of the body to which we cannot devote our direct gaze. It only happens by reflex or if others have done it for us. This project combines two aspects of my photographic work: the body and the portrait. In fact, these backs are thought of as portraits, where instead of a face we see a back expressing itself.

TONI PETRASCHK

Creeping Border

The border region between Georgia and South Ossetia is characterized by steppelike plains and hilly landscapes. The inhabitants can glimpse the peaks of the Great Caucasus. Sometimes Russian soldiers appear here, draw barbed wire and define a new boundary line. On the surface, the creeping occupation remains hidden from the eye — until the neighbor’s house is suddenly in another country. This practice drives the border demarcation on Georgian terrain — and thus creates facts that can hardly be contested.

South Ossetia has broken away from Georgia as a de facto republic, but is recognized internationally as independent by only a few countries, most notably Russia. After two wars — in 1991/92 and 2008 — between Georgia and Russianbacked South Ossetia, the final secession from Georgia and the erection of a barbedwire-proof border fence and permanent stationing of Russian troops in South Ossetia occurred in 2008. Since then, this border has been an almost impassable demarcation line between the parties to the conflict, confronting thousands of Georgians who have fled their homes with the prospect of never being able to return.

But this border is anything but a static dividing line: its shape varies greatly, ranging from barely recognizable landmarks to rolls of barbed wire to iron border fences with warning signs and surveillance cameras. It is not uncommon to see arrests and interrogations of Georgian citizens who unknowingly cross the border.

These are the civilians who have had to live with the effects of the conflict between Georgia, South Ossetia and Russia for over fifteen years. What lies under the surface of this cold conflict? And ultimately: what gives those affected the strenght to go on about their daytoday work — living in the uncertainty of a moving border?

A question even more urgent to ask, given the ongoing russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

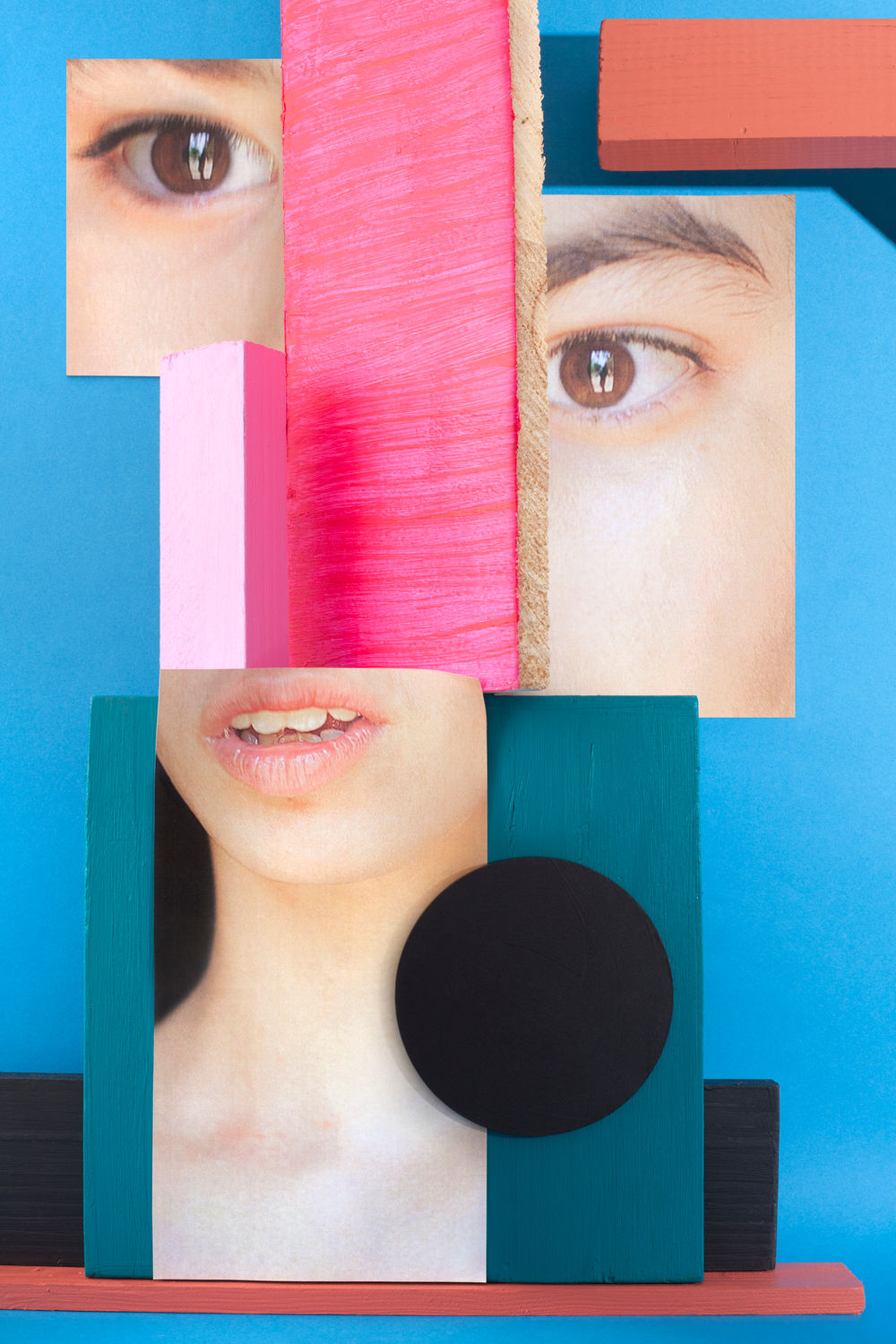

LISA PRAM

Cuerpos (Bodies)

23° skin

CUERPOS (Bodies) is a series of photographs created between 2021 and 2022 in which I explore the act of getting aware of one’s own physicality. My artistic practice revolves around the concepts of unpredictability, the randomness with which we occupy a place in the cosmos, and how chance affects our existence. CUERPOS raises questions around the corporeal and the temporary, in order to reflect on some of these huge enigmas of life.

I am interested in the act of being and existing from a tactile and existential standpoint. I depict the human body and face as a container of emotions, ideas, stories but also the bones, organs and cells lying under the surface. I place an image of a body, face or bone as a measuring stick within a set of humble materials such as painted pine wood slats, cardboard and printedpaper. I place it in variations of perspective and scale, firstly to mislead the eye and explore the limits of perception, and secondly to investigate how we fit our bodies into structures that can be physical and, overall, mental. The constructed installation functions as an ephemeral collage that I disassemble immediately after the shot, leaving the photographic medium the responsibility of registering its existence, the moment that will never exist again.

The amount of degrees mentioned in the titles are used to indicate the width of the angle occupied by the body, face or bone, on the twodimensional image.

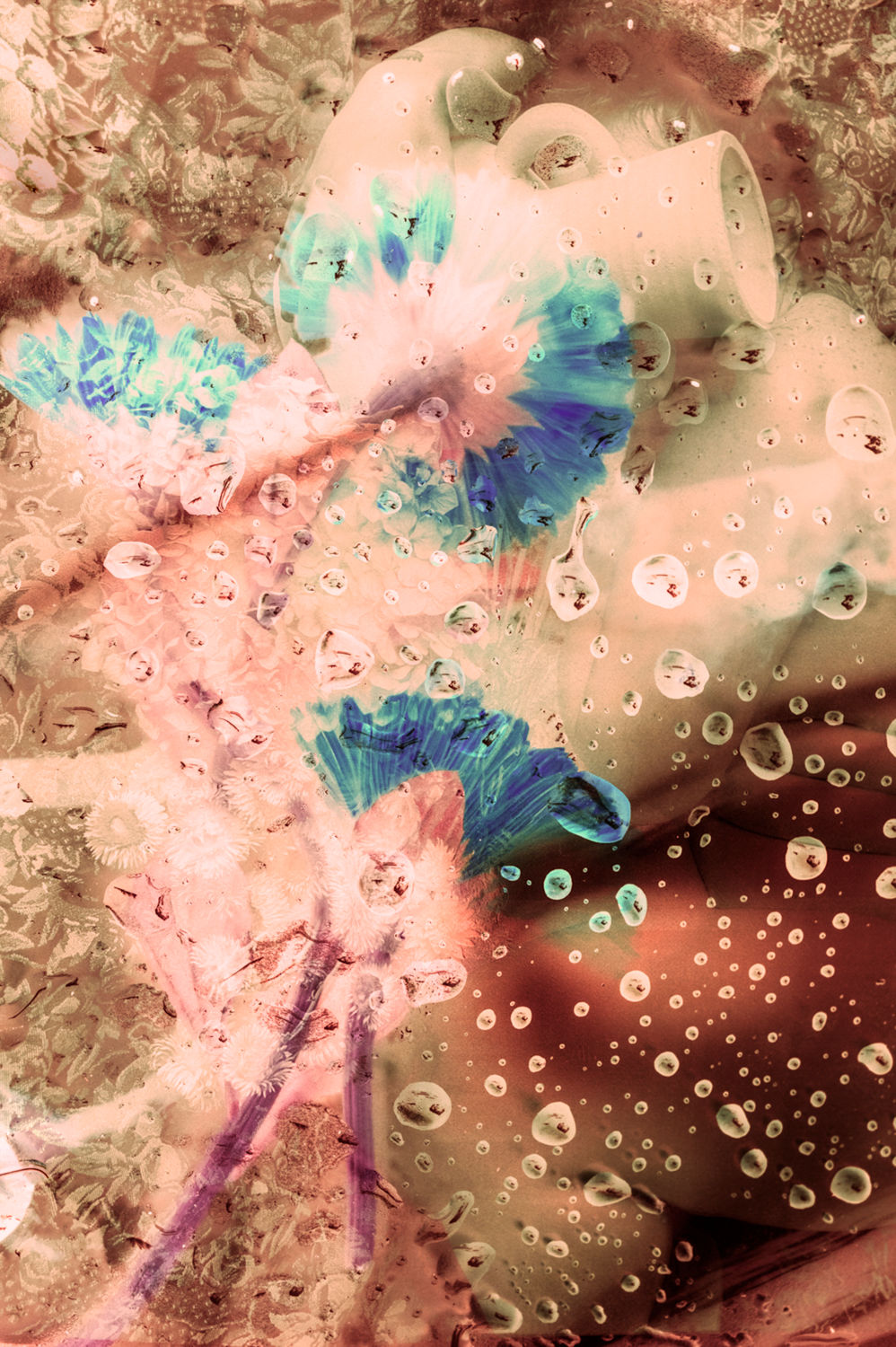

ANN PROCHILO

This Is Water

Red

This Is Water explores selfawareness and its nemeses: blind certitude and unconsciousness.

It is inspired by a story shared by David Foster Wallace in a commencement speech: “There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, ’Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, ‘What the hell is water?’”

I love this parable and its reminder that essential things are all around us, hidden in plain sight. This project examines what is above and below the surface, shifting mediums and bending light. It seeks to illuminate the malleable foundations upon which we make meaning and take actions that impact ourselves, others, and the environment.

I use water to depict transitional moments that precede transformation — those potent and vulnerable moments before something emerges, or does not. Water reveals and water hides. It points to ways in which we are egodeluded and dissociated from ourselves — drawn, as to a siren’s call, to an anesthetized oblivion. While it is possible to correct for optical distortions caused by light passing through water, I choose not to. I embrace refraction, diffusion, and reflection in service to illusion. To the extent that dissonance is an uncomfortable, but necessary starting place for selfawareness, it is my thesis that grappling with ambiguities is a powerful tool for awakening.

Just as the struggle for transformation defines my quest, it defines each person’s journey between unconsciousness and selfawareness. I believe our task as human beings is to wake to ourselves and the waters in which we swim so that we may choose right action.

For me, that means not foundering in a sea of willful ignorance or being rendered mute by those who would drown my voice. And like our two young fish, it means swimming along, constantly reminding myself that “this… is water.”

EMMA SARPANIEMI

Two Ways to Carry a Cauliflower

Self-portrait Wearing Red Socks

Two Ways to Carry a Cauliflower (2021–) is a performative photo graphy series exploring women‘s selfportraiture. To free the subject (and the gaze) from certain patriarchal ideals of femininity, Emma Sarpaniemi creates a playful and tender representation using herself as the character to behave, look and perform on her terms and rules. Sarpaniemi creates an image of a woman which is blurred between her identity, reality, and fantasy. The series is a playful and modern yet timeless portrayal of womanhood.

URSULA SOKOLOWSKA

Multiples

Self Portrait #159

In Multiples, I use various camera formats (film and digital), 35 mm slide projections, and multiple exposures to construct a fiction around the deliberate act of remembering.

CECILIA SORDI CAMPOS

The motherhood that wasn’t

à luz #8

I’m infertile. While I never wished to be a mother, the concept of infertility is part of my quotidian reality. I question if this is due

to social expectations or a biological need. Since having children has never been an intention, my infertility should not cause any emotional conflict, nonetheless, it does. My body, it seems, has failed to conform to the social and biological expectations of a person who was born with a reproductive apparatus. I am yet to find women who share similar emotional conflict, and I question the reason these issues may continue to be contentious. There are other women experiencing similar difficulties, so why do I continue to feel isolated?

With the making of this project, I seek to understand my lived experiences of infertility caused by endometriosis. Using my menstrual blood as a drawing medium, I aim to uncover ways in which it can be used as an aesthetic, political expression that serve as a physical record of catharsis — a mourning over the choice I was unable to make rationally, the choice my own body took from me.

My hope for this project is that by chronicling my lived experiences of infertility, I am able to contribute to public discourses by offering a personal view that help erode the perspectives that are subjugated by shame.

IVONNE THEIN

discobedient bodies

When people meet in everyday life, they also perceive themselves as bodies. In our performanceoriented society, there is a growing tendency towards an objectification that encodes the body as a mass that can be manipulated at will. We can do something with our body, shape it or manipulate it. Artificial body extensions (prostheses) have long been socially accepted, even if they are only used for selfexpression or selfoptimization. Aging or illness are considered stigmatization and should be stopped or hidden as much as possible.

Photography plays an important role in spreading idealized body images, as the flood of images fuels the dream of a young, healthy, and flawless body. In the work disobedient bodies, I confront the viewer with photo graphic images of sick or old bodies and combine them with artificial body parts or tools for body optimization.

I see these photographs as a counterpoint to the hyper real, perfect body images we encounter daily in mass media.

AMY TOUCHETTE

Personal Ties: Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn

Photographing strangers on the street is like having an epic novel read aloud to you, only it’s real. You’re connected. You’re involved. And you carry every piece of it with you from then on. I started photographing people in my adopted neighborhood, Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, soon after moving here in 2015. I’ve always used photography as a way of meeting people, and I was especially drawn to the residents of Bed-Stuy, who foster the most inclusive feeling of community I’ve experienced in my 24 years of living in New York City. Friends, couples, family members, chosen or not, often caught my eye. Portals into both Bed-Stuy and humanity at large, these acutely personal ties are both unique and universal, and they’re also the driving force behind the perseverance of this community.

In street portrait photography, the very fact that exchanges are short and anonymous is what makes them so meaningful. Far deeper than a hello or good morning, making a portrait with a stranger is a profound, unique burgeoning of connection that reminds me never to give up on humanity. Having these experiences right outside my front door, in a place I call home, whose sidewalks I sweep, and bodega employees I wave to, and collective pain and joy of daily life I seep in, these transmissions of trust become something more: they become personal ties, too.

There’s a great deal that these photographs don’t show, including the long and winding process and experience of making them: the voices I heard, and faces I saw, and interactions that took place during my many miles of walking the streets of Bed-Stuy that aren’t recorded here. I’ve heard of photographs being like trophies, awards for actually going out there and doing it. But for me photo graphs are simply what’s shareable of an experience too complex, too multisensorial, too much of every aspect of life to possibly impart. They are the cream that rises to the top, while all the rest — all that wasn’t photographable — supports and lifts them.

SEBASTIAN WELLS & VSEVOLOD KAZARIN

Portraits from Kyiv, Ukraine, April and May 2022

Yelizaveta and Mark

When Vsevolod Kazarin, a fashion photographer, and Sebastian Wells, a documentary photographer, met in Kyiv, they decided to team up and combine their skills. Being both interested in the young gen eration of creatives in Kyiv, they started to work on a series of portraits that focuses on young people that don’t stop self-expressing their identities through their fashion. While using the means of documentary photography and portraying the protagonists out of the situation and in their respective environment, are a witness of a historical moment.

GUANYU XU

Resident Aliens

In my ongoing project Resident Aliens, I find participants who hold different visa statuses in the United States. Upon invitation, I photograph their homes and personal belongings, and then print these images out in addition to my subjects’ personal photo archives. These prints are installed back into their space as temporary installa tions and additionally documented as photographs. They become the synergy of portrait and space.

It is from my own experience and the accumulation of similar stories from my friends that drove me to start Resident Aliens. The creation and the use of fear psychologically control us. A resident alien, who is required to pay the same tax as a citizen, may not only need to struggle for assimilation in the public space but also cannot see the home as a safe haven. The construction of state power perpetually classifies immigrants as potential subjects of criminality. The pandemic even added more difficulties for many people I photographed.

My collaboration with participants is not only an integral social practice in representing their complex identities and histories, but it’s also a negotiation of power and assumed stereotypes. As a foreigner, entering their territory, I transform their temporary states of being into installations and preserve the constructions as photo graphs. The project presents immigrants’ intimately nuanced experiences within their homes and in the US at large. These convergences of spaces and times invite the viewer to enter into spaces of fluidity rather than fixed perspectives. They mobilize the viewer’s gaze, imagination, and care, defying strict definitions.

Through collaboration and conversation, Resident Aliens presents the complicated conditions immigrants experience in the U.S. I want to ask: In this interconnected world, how do we redefine citizenship and the legality of a person?

All series can also be found in our current catalogue.